Why Systems Thinking is so Important in the Circular Economy

And how circularity isn't just about fixing parts but also rethinking the whole

Hi there! Welcome to The Edit: Perspectives. This is where I drop a weekly deep dive into an idea or theme shaping the way we think about people, planet and business. Each edition explores a single idea or tension point - drawing on research, case studies and reflections - to challenge assumptions and open up new ways of seeing the world. Less news, more perspective.

New here? Thanks for joining me! This button is for you ⬇️

“Pull a thread here and you’ll find it’s attached to the rest of the world.”

― Nadeem Aslam

Sustainability challenges are infamously complex, multifaceted and difficult to solve. This is because the problems are interconnected and often impact many sectors, affect communities to varying degrees, and if you scale up one solution, a new problem may emerge as a result.

For example, the fashion sector’s waste problem isn’t just about ‘too many clothes.’ It’s a tangled web of cheap production, globalised supply chains, constant trend cycles and consumer identity all wrapped up in a neat, beautiful bow. Even well-meaning interventions (like recycling programs or sustainable fabrics) barely touch the root cause on their own because the current system rewards overproduction and rapid consumption.

Similarly, the economy, society and environment aren’t separate, but rather, nested systems. Businesses depend on people power to function and thrive → people depend on a healthy environment for food, air and stability → and the environment depends on the balance of its natural equilibrium to stay intact to keep feeding itself and societies. And so goes the cycle of the system.

When one overdraws from another, for example, when businesses extract more value than the environment or societies can regenerate, the feedback loops eventually snap back: resource scarcity, social unrest, regulatory pushback, reputational damage. Conversely, when businesses align profit with planetary and social wellbeing, they strengthen the entire system’s resilience. Circular economy thinking builds exactly on this logic by designing products, services and systems that regenerate rather than deplete over time.

The problem with linear thinking

Linear thinking tells us that problems can be fixed one part at a time. In fashion, that looks like swapping one material for another or launching a recycling take-back program while the rest of the system keeps churning out cheap clothes at record speed. Each fix treats the symptom and not the structure. This results in waste piling up faster than any recycling scheme can handle, while overproduction keeps climbing because the system is rewarded for selling more, not better.

The core flaw of the linear mindset is that it aims to resolve the sustainability problems it creates by a series of quick fixes. It’s like we are playing a never ending game of ‘whack-a-mole’ – where one problem disappears, another quickly emerges.

When we zoom out, it becomes clear that waste isn’t a mistake, but rather an outcome of how the system is designed. Systems thinking helps us spot those feedback loops, like how marketing drives demand, demand drives overproduction and overproduction drives waste, and helps us design interventions that flip the system inside out and upside down.

What systems thinking actually means

So, what does systems thinking actually mean? Well, essentially, systems thinking is ‘the ability to understand how the parts of a system interact to produce the behaviour of the whole.’ You are not taking the event or thing at face value, but rather, you are looking beneath the surface to find what’s really impacting it and driving it to inform your understanding of the whole.

Think of it as looking at an iceberg – you can only see the top of the iceberg, yet below lies far more to it than originally known. In this way, systems thinking helps us to subvert and challenge our existing biases and assumptions with which we view the world and asks us to look further to understand how different parts of problems are interconnected and to understand patterns of system behaviour over time.

If you pay attention, you can see systems all around us. Bees, for example, aren’t just cute little insects that make honey – they are the world’s little warriors and protectors for making our ecosystems work. As pollinators, they link plants, food systems and biodiversity all around the world. Their activity feeds 75% of the world’s leading food crops. When bee populations fall, the catastrophic impacts can be felt across the entire ecosystem value chain. Crops yield less, farmers rely more on chemical inputs, food prices rise and ecosystems lose resilience. The health of bees is a mirror of the entire system’s health. Protecting them means we also protect the precious and fragile balance of our world’s ecosystem.

How systems thinking strengthens circular transitions

Systems thinking helps circular initiatives move from isolated projects to true transformation. First, it targets root causes rather than symptoms. Instead of designing better recycling schemes, it asks why waste exists in the first place. This often reveals issues in product design, overproduction or consumption habits. Addressing these fundamentals reduces costs, builds resilience and sparks innovation by redesigning the system and not just the output.

Taking the fashion sector again as an example – by mapping the entire fashion system from raw material extraction to retail incentives and consumer psychology, we see that waste isn’t a design flaw, it’s a design outcome. A systems approach suggests leverage points:

Slow fashion business models (rental, resale, repair)

Extended producer responsibility policies

Shifting marketing away from disposability

Redesigning incentives around use per item, not sales per season

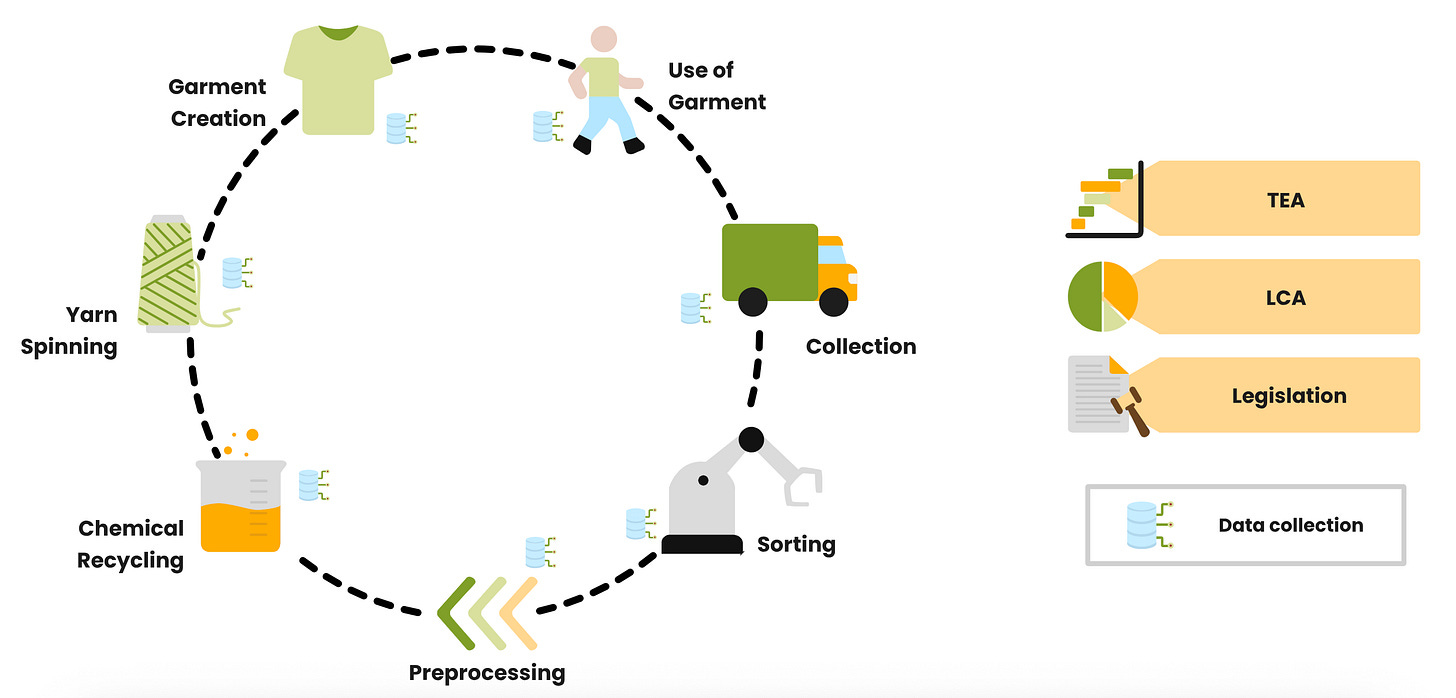

Second, systems thinking builds collaboration and shared insight. Circularity happens not only within companies, but also between them. One such example is the T-REX Project, which brought together 13 major companies from across the fashion value chain to collaboratively work towards a scalable solution to textile recycling. The three year project created a blueprint for scaling textile-to-textile recycling in Europe, and it highlights the power of collaboration through alliances. No single organisation can close a loop on its own. It takes networks and alliances to help uncover the full picture.

Finally, systems thinking prevents rebound effects and short-term fixes. A new bio-based material may lower emissions but increase deforestation elsewhere. By mapping these feedback loops, businesses can spot unintended consequences before they scale, keeping sustainability efforts credible, measurable and future proof.

The cost of ignoring it

Many businesses claim to be ‘going circular,’ yet most initiatives remain surface-level through implementation of recycling pilots, new sustainable packaging lines or resale platforms and programs. While these initiatives are needed and every little step of progress is hugely important, they often stall or create little impact in the grand scheme of things because they tackle symptoms in isolation.

For example – if a fashion company introduces a new resale or repair program, that’s great! BUT, is that same company also looking at how best they can redesign their products for durability? Are they also looking at how they can valorise their waste? Are they also looking at how they can decouple revenue growth from over consumption and over production of products? If not, then they are merely pulling at a single thread and refusing to follow it to the bigger picture.

Further, without a systems lens, circular strategies can even create new problems. For example, recycled materials may have higher carbon footprints, or transitioning to 100% cotton or wool fabrics can further exacerbate environmental impacts.

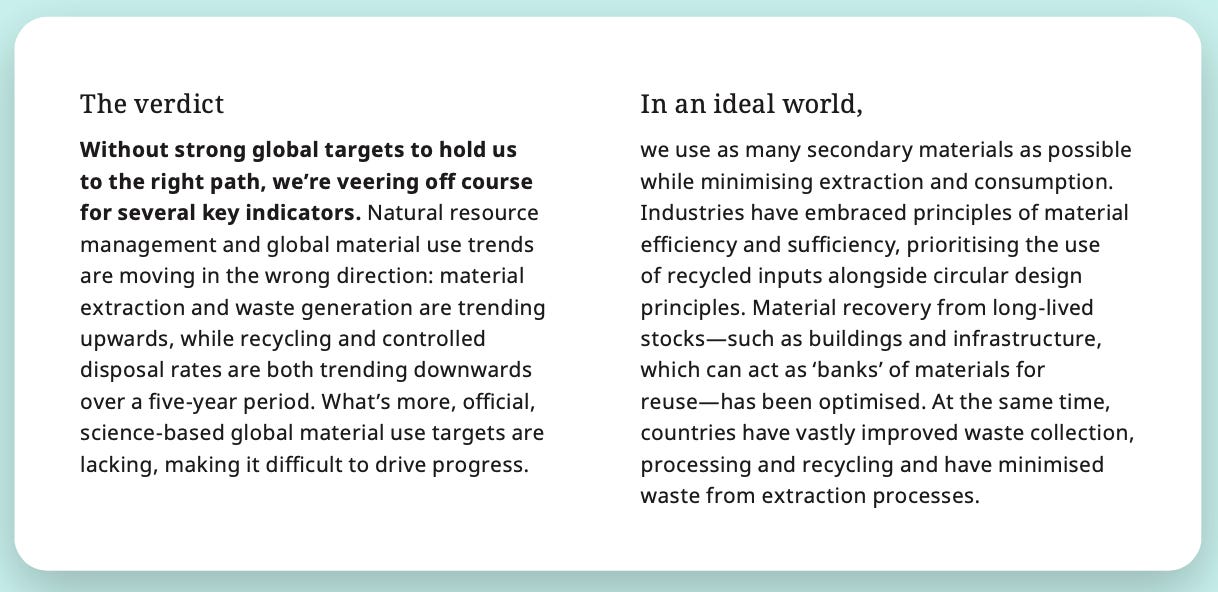

According to the Circularity Gap Report 2025, the global economy is only 6.9% circular, down from 7.2% in 2024, highlighting a continual downward trend since 2018. This shows that linear thinking persists under circular branding. Ignoring systems thinking doesn’t just limit progress, it also wastes time, capital and erodes public trust. While circular economy has never been more front of mind globally, why then are we becoming less circular as a global society?

What a systemic approach looks like

A systemic approach starts by zooming out to understand how materials, value and decisions move through an ecosystem. By zooming out, we can ask ourselves what future are we trying to enable and what feedback loops need to shift to get there?

In practice, this means reimagining supply chains as shared networks rather than linear pipelines. It means re-aligning incentives so waste becomes a resource and success is measured by regeneration and not just profit. In fashion, it’s shared repair infrastructure, resale platforms, or textile-to-textile recycling facilities that help close loops.

In policy, it’s regulation that links environmental, social and economic goals rather than treating them separately. The EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products (ESPR) is a great example of this. It not only looks at recycling downstream in value chains, but it also looks at designing products for durability, reusability, upgradability and repairability from the outset, limiting the generation of waste, addressing the presence of substances that prevent circularity, making products easier to remanufacture and recycle, making products more energy and resource efficient, and improving the availability of information on product sustainability. In this way, it looks at the entire system, rather than addressing just one part.

Conclusion

And so, we discover that the key to systems thinking is interconnection. Resultantly, systems thinking gives the circular economy its depth and direction by reminding us that sustainability isn’t just about perfecting parts but also about harmonising the whole. Linear thinking built efficiency, whereas systems thinking builds resilience. It helps us design with awareness of cause and effect, flow and feedback. The shift is subtle yet profound. We move from ‘how do we make less waste?’ to ‘how do we create systems where waste is a resource?’ Circularity, at its heart, is a systems story, one where we see differently, connect deeply and design economies that work like the ecosystems we depend on: adaptive, regenerative and circular.

Have a hot take? Please share it with me below!

If you enjoyed this edition of The Edit: Perspectives, you can support my work by subscribing or pledging to my Substack, leaving a comment, or sharing it with a friend. Each small effort helps others find their way to The Circular Edit. I appreciate you reading and coming along the journey with me 🤍

If you’d like to connect, you can find me on LinkedIn.

Want to dive deeper down the rabbit hole? I found the below article interesting:

Another great article and perspective. As I was reading it I kept thinking about my days in the business improvement space, particularly around the application of Lean Manufacturing through systematically reducing waste, improving resource efficiency, and enhancing the longevity of products and materials. However, as you have pointed out it needs to be viewed holistically at a level where the complete connectivity can be seen and resolved towards the circular economy.